The below article appeared in the Detroit Free Press Sunday Magazine on August 30, 1987. The full text is below, and scans of the original piece can be found following it.

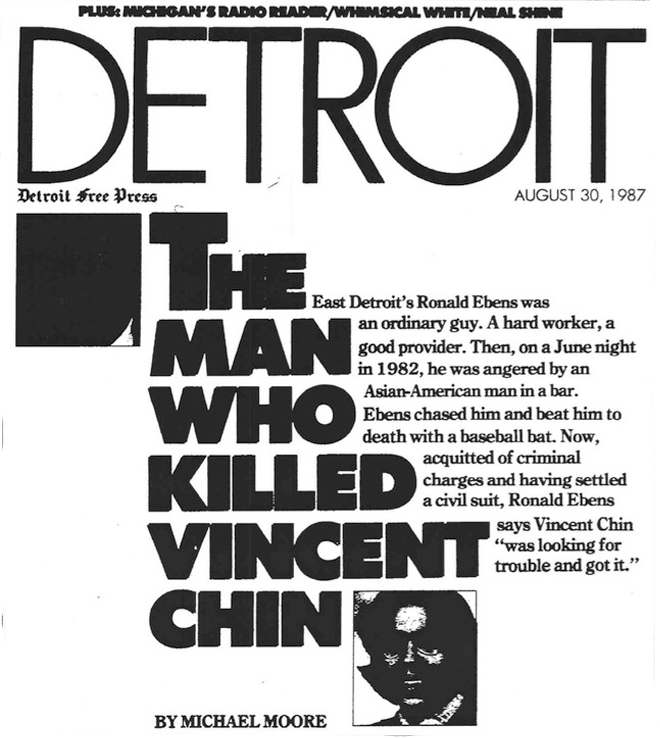

THE MAN WHO KILLED VINCENT CHIN

By Michael Moore

The Detroit Free Press, August 30, 1987

East Detroit’s Ronald Ebens was an ordinary guy. A hard worker, a good provider. Then, on a June night in 1982, he was angered by an Asian-American man in a bar. Ebens chased him and beat him to death with a baseball bat. Now, acquitted of criminal charges and having settled a civil suit, Ronald Ebens says Vincent Chin, “was looking for trouble and got it.”

Ronald Ebens killed Vincent Chin, a Chinese-American, five years ago with a baseball bat, and he never served a day in jail. Now he claims he can’t understand why the whole Asian-American community is angry. “I don’t even know them,” he says. “… I’ve never been around them. The only ones I had ever met are the ones in the Chinese restaurants, and they were always nice and I was always nice to them.”

THE WAGES OF DEATH

By Michael Moore

The man who killed Vincent Chin is in fine fettle on the morning of July 31. With reason. The system has worked to his advantage once more, and he is elated. Having won acquittal on federal civil rights charges months earlier, the civil suit filed by the slain man’s family has been his only remaining hassle. Now a settlement has been reached. “That’s it, it’s over!” he exclaims. “Done. Finished. Over! Yeah!” He can barely contain his excitement, sounding like a fan whose baseball team has just won the pennant. Then he turns sarcastic and adds: “About all that’s left to charge me with now is rape.”

Ronald Ebens, 47, a former Chrysler Corp. employee, used a baseball bat to club Vincent Chin, a young Asian-American man, to death in front of a Highland Park McDonald’s five years ago. Chin, 27, celebrating with his pals that night, was to have married Vicki Wong the next day.

Now, five years and a few weeks later, it is Ebens who celebrates, even though he has just agreed to a $1.5 million settlement under which he would pay $200 a month for two years, beginning Sept. 1. Then he would start paying $200 a month or 25 percent of his net income, whichever is more.

Any new income or sudden financial gains —such as an inheritance— would be subject to the judgement: the sale of his home would not.

And while that sounds like a significant penalty, Ebens is overjoyed. The terms of the settlement, he points out, require him to pay only if he has a job.

Ron Ebens hasn’t had one in five years; he doesn’t expect to have one in the near future. The Chin family, he says, “can’t get blood from a stone.”

“It is my fervent wish,” Ebens deadpans, “that I live long enough to pay off the entire amount.”

“That’ll be when I’m 672 years old.”

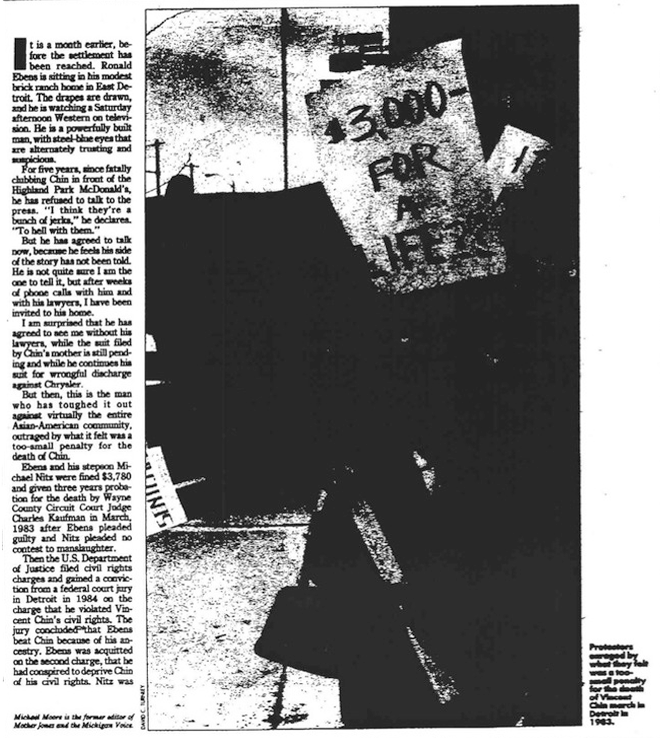

It is a month earlier, before the settlement has been reached. Ronald Ebens is sitting in his modest brick ranch home in East Detroit. The drapes are drawn, and he is watching a Saturday afternoon Western on television. He is a powerfully built man, with steel-blue eyes that are alternately trusting and suspicious.

For five years, since fatally clubbing Chin in front of the Highland Park McDonald’s, he has refused to talk to the press. “I think they’re a bunch of jerks,” he declares, “To hell with them.”

But he has agreed to talk now, because he feels his side of the story has not been told. He is not quite sure I am the one to tell it, but after weeks of phone calls with him and his lawyers, I have been invited to his home.

I am surprised that he has agreed to see me without his lawyers, while the suit filed by Chin’s mother is still pending and while he continues his suit for wrongful discharge against Chrysler.

But then, this is the man who has toughed it out against virtually the entire Asian-American community, outraged by what it felt like was a too-small penalty for the death of Chin.

Ebena and his stepson Michael Nitz were fined $3,780 and given three years probation for the death by Wayne County Circuit Court Judge Charles Kaufman in March, 1983 after Ebens pleaded guilty and Nitz pleaded no contest to manslaughter.

Then the U.S. Department of Justice filed civil rights charges and gained a conviction from a federal court jury in Detroit in 1984 on the charge that he violated Vincent Chin’s civil rights. The jury concluded that Ebens beat Chin because of his ancestry. Ebens was acquitted on the second charge, that he had conspired to deprive Chin of his civil rights. Nitz was acquitted on both charges.

U.S. District Judge Anna Diggs Taylor sentenced Ebens to 25 years in prison, but the U.S. Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the conviction. Taylor ordered a change of venue to Cincinnati and reheard the case there. In May, the second jury acquitted him, thus ending any further criminal prosecution of Ronald Ebens.

If he got through all of this without a scratch, what harm could an interview do? As he sees it, “The guy who walks away without getting hurt is the guy who has won.”

By his standards, Ronald Ebens has been winning a lot lately, and talks that way. “If he (Chin) hadn’t started it, he’d still be alive,” says Ebens. “I mean, don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying it’s right that he died. All I’m saying is that if he hadn’t started it, he’d still be alive. They were looking for trouble and they got it.”

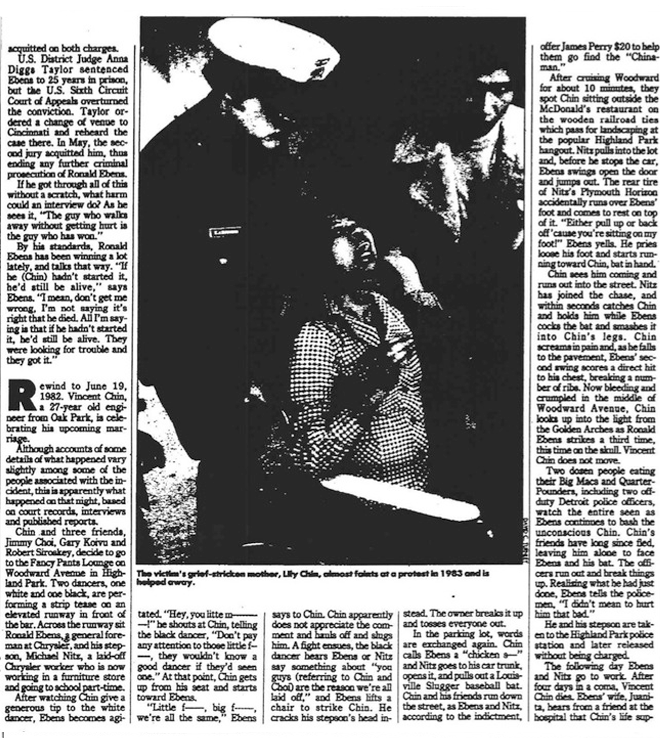

Rewind to June 19, 1982. Vincent Chin, a 27-year-old engineer from Oak Park, is celebrating his upcoming marriage.

Although accounts of some details of what happened vary slightly among some of the people associated with the incident, this is apparently what happened on that night, based on court records, interviews, and published reports.

Chin and three friends, Jimmy Choi, Gary Koviu and Robert Siroskey, decide to go to the Fancy Pants Lounge on Woodward Avenue in Highland Park. Two dancers, one white and one black, are performing a strip tease on an elevated runway in front of the bar. Across the runway sit Ronald Ebens, a general foreman at Chrysler, and his stepson, Michael Nitz, a laid-off Chrysler worker who is now working in a furniture store and going to school part-time.

After watching Chin give a generous tip to the white dancer, Ebens becomes agitated. “Hey, you little m———–!” he shouts at Chin, telling the black dancer, “Don’t pay any attention to those little f——, they wouldn’t know a good dancer if they’d seen one.” At that point, Chin gets up from his seat and starts towards Ebens.

“Little f—–, big f—–, we’re all the same,” Ebens says to Chin. Chin apparently does not appreciate the comment and hauls off and slugs him. A fight ensues, the black dancer hears Ebens or Ntiz say something about “you guys (referring to Chin and Choi) are the reason we’re all laid off,” and Ebens lifts a chair to strike Chin. He cracks his stepson’s head instead. The owner breaks it up and tosses everyone out.

In the parking lot, words are exchanged again. Chin calls Ebens a “chicken s—” and Nitz goes to his car trunk, opens it, and pulls out a Louisville Slugger baseball bat. Chin and his friends run down the street, as Ebens and Nitz, according to the indictment, offer James Perry $20 to help them go find the “Chinaman.”

After cruising Woodward for about 10 minutes, they spot Chin sitting outside the McDonald’s restaurant on the wooden railroad ties which pass for landscaping at the popular Highland Park hangout. Nitz pulls into the lot and, before he stops the car, Ebens swings the door open and jumps out. The rear tire of Nitz’s Plymouth Horizon accidentally runs over Ebens’ foot and comes to rest on top of it. “Either pull up or back off ‘cause you’re sitting on my foot!” Ebens yells. He pries loose his foot and starts running towards Chin, bat in hand.

Chin sees him coming and runs out into the street. Nitz has joined the chase, and within seconds catches Chin and holds him while Ebens cocks the bat and smashes it into Chin’s legs. Chin screams in pain, and as he falls to the pavement, Ebens’ second swing scores a direct hit to his chest, breaking a number of ribs. Now bleeding and crumpled in the middle of Woodward Avenue, Chin looks up into the light from the golden Arches as Ronald Ebens strikes a third time, this time on the skull. Vincent Chin does not move.

Two dozen people eating their Big Macs and Quarter-Pounders, including two off-duty Detroit police officers, watch the entire scene as Ebens continues to bash the unconscious Chin. Chin’s friends have long since fled, leaving him alone to face Ebens and his bat. The officers run out and break things up. Realizing what he had just done, Ebens tells the policemen, “I didn’t mean to hurt him that bad.”

He and his stepson are taken to the Highland Park police station and later released without being charged.

The following day Ebens and Nitz go to work. After four days in a coma, Vincent Chin dies. Ebens’ wife, Juanita, hears from a friend at the hospital that Chin’s life support systems have been turned off. She waits until Ebens has finished his supper before she breaks the news.

“Vincent died today,” she says calmly. Ebens puts down his fork, finishes chewing his food and is silent for a long time. He does not cry.

It is now almost five years later to the day. Ronald Ebens leans back in his easy chair, cranks the handle that produces the retractable stool, and pleads for a little understanding.

“People are wrong about me, period,” he says. “I am not the way I’ve been made out to be. I’m easy, you know. I’m a pushover. I’m a pussycat.” These words do not flow effortlessly from Ebens’ mouth.

“I’m a macho, and it’s hard for me to admit that I’m really just a pussycat.” He is not, he insists, some maniac who, “just goes down clearing the streets of Asians.”

Ebens’ memory is fuzzy about the night he killed Chin, but he does have a clear recollection of Chin’s friend, Jimmy Choi. “This little Jimmy Choi,” he recalls, “he’s like a little pest, that’s what he amounted to. He was just running back and forth, running his mouth, just keeping things agitated. He was one of those little guys that just — hey, you ever see this commercial on TV with the two dogs? That Kibbles ‘N’ Bits commercial with the little dog jumping over the big dog, saying, ‘Come on, Spike! C’mon Spike!’ That’s what that guy reminded me of.”

Ebens’ voice is filled with contempt, and he sweeps his fingers off the top of his thumb, the way one flicks away a particle of something unpleasant.

I ask him about how he killed Chin.

“He took off running, and I hollered at him, ‘You son of a bitch!’ He ran out into the street and Mike (Nitz) ran right into him and grabbed him. I think I probably hit Chin in the leg or something, and the only thing that’s ever made any sense in my mind is that, as he started to go down, I must have caught him in the head (with the bat).”

“All I wanted to do was inflict a little injury, to get even for Mike’s split head.”

Ebens grows very quiet. His concentration is broken by a small army of red ants crawling on the end table beside his chair. “Damn, would you look at this!” he says to his wife. “Where did these things come from?” With his fingers he begins to crush the ants, one by one, wiping their residue on his jeans.

“I just don’t like ants — the little suckers,” he says.

“Little suckers, like ‘little f——?’” I ask. Ebens smiles and looks nervously at the tape recorder I have running.

“I gotta get some spray,” he says, cranking the handle of his chair. “Say, you look so familiar to me. I’ve seen you somewhere before.”

“I don’t think so,” I say.

Wayne County Circuit Judge Charles Kaufman’s decision to let Ebens and Nitz go with a $3,780 fine decision enraged the Asian-American community throughout the country. The American Citizens for Justice was formed to pressure Kaufman into reconsidering the sentence, which he eventually refused to do. Ronald Ebens has a vivid memory of the day he was to be sentenced.

“I told my wife that morning she might as well put a stamp on my a– ‘cause they were going to be sending me away. (When Kaufman announced the sentence) you could have knocked me over with a feather.”

It was from that moment, that Ebens believes he, “became a symbol for the Chinese. It was totally uncalled for. They were trying to hang me. What would have been gained by sending me to prison except to appease them?”

“They blew it (the killing) all out of proportion. Vincent and I were just in the wrong place at the wrong time, and it’s too bad, you know, especially for him. At least I’m alive.”

“But they (the Asian-American groups) used the press, they used the federal government, they sued everybody on this thing. I don’t know who the hell they are, and I have absolutely no use for them.” Ebens notices that the level of his voice has risen a few decibels and he quickly regains a modicum of composure.

“I don’t hold the Asian mass responsible for the actions of these few people,” he adds, in a forgiving tone.

Ebens contends that the Asian-American groups put him through “four years of hell with a bunch of damn lies.” he denies that he said anything of a racial nature to Chin that night. He has tape recordings his lawyers subpoenaed from the American Citizens for Justice (ACJ) which seem to indicate that the Asian-American group sought to influence the witnesses to tell a consistent story on the stand. On the tapes, the attorney for the ACJ, Liza Chan, can be heard apparently trying to coax Choi, Koivu, and Siroskey into corroborating each other’s statements. Only after Kaufman’s sentencing of Ebens — and his meeting with Liza Chan — did Jimmy Choi claim to have heard Ebens make ethnic slurs against Vincent Chin.

Contrary to what he calls these “lies” about racist remarks, Ebens says he was actually upset at Chin for discriminating against the black dancer by giving her the smaller tip, and that he was acting as sort of a one-man civil rights commission at the Fancy Pants.

“This black girl dancing was a knockout, OK? Now if you think Mike and I are going to be sitting there making comments about the car industry with her dancing there, well, you got to be some kind of wimp. I mean, get serious.”

The ants return to the end of the table, this time in force. For the remainder of the interview, Ebens gently picks them off, five or six at a time.

Ronald Ebens was born and raised on a farm in northern Illinois. Married at the age of 18, “just like everybody else,” he spent 2 & 1/2 years at the Army Air Defense School. When the Vietnam war began, he wanted “no part of it,” so he decided not to re-enlist. He came home to Illinois and went to work for Chrysler in Belvedere. A promotion brought about his move to Detroit, and, after divorcing his first wife, he married Juanita in 1971. Eventually he was made a superintendent. He had 17 years seniority within the company when he was fired after his conviction.

Ebens believes he has been made to suffer because the Asian-American community needed a cause to rally around. “To put somebody through what I’ve been through, just for a cause, that’s wrong,” he says, shaking his head and clenching his fist.

Although Ronald Ebens never spent a day behind bars, it would not be entirely accurate to say that he hasn’t been punished. First, he was fired from Chrysler, “because,” he says, “the company didn’t want to take any flak.” He is bitter that after, “being told from 6 o’clock in the morning to 6 o’clock at night for 17 years that we’re a team, we pull together, we take a pay cut, we have all this s— beat into us and then what do they do…?” He takes his right hand and brings it down hard on his other hand, creating a loud POP! “Somebody’s a loyal employee, you never fire them.”

Ebens has not worked for five years. He has spent most of his time around the house while his wife has worked at the furniture store where her son, Mike Nitz, is employed. “Imagine what this has been like for me,” he asks. “Every day I have to get up and put my life back together again.” He says he has grown very depressed at times, even suicidal, and has sought the help of a “psychologist friend who has taught me a few tricks on how to deal with the stress, like lifting weights and running.” He says he didn’t commit suicide because he didn’t want to, “give anybody the satisfaction of thinking, ‘Man, we made the guy give up.’ I’m just not a quitter.”

Ronald Ebens believes he has beaten “the cause,” and the cause was him. I ask him why he thinks the Asian-American groups would want to use him in this way.

“To show the plight of the Asian-American in America,” he responds. What is that plight, I inquire. “Hey, I didn’t even know there was one, that’s how dumb I am. I still don’t know what their plight is. Obviously, they’re shooting for something.” I ask him what they are shooting for. He is becoming perturbed.

“I don’t know… Do you see any Asian-Americans around here? I don’t even know them. I don’t know what their plight is. I’ve never been around them. The only ones I had ever met are the ones in the Chinese restaurants, and they were always nice and I was always nice to them.”

Ronald Ebens believes that, “everybody has some racist feelings — you, the Chinese, everyone. I can’t honestly say I harbor any feelings against any ethnic group, OK? That doesn’t mean I want to live with them, OK?”

In East Detroit, where Ebens lives, (and he wants it noted that East Detroit is not the east side of Detroit — “No way, we’re like Roseville”) there are, by his count, only three black families. Juanita points out that somebody has accused the East Detroit police department of discriminating because it has no blacks on the force.

“Well, if we’re supposed to hire on a percentage basis,” Ebens observes with a chuckle, “then they got just enough (black officers).” He stresses that he is not absolutely opposed to affirmative action and feels it is needed “someplace like down in Alabama where they have been passed over just because they were black. But then it is taken to the other extreme where they are promoted over the white guy who has a higher score and stuff, and I don’t think that’s right at all.”

The white-guy-as-victim syndrome has become Ronald Ebens’ reality. There were no racial comments made in the bar that night, he insists. He was not thinking about the decline of the American auto industry or Japanese imports while Racine, the dancer, shed her bikini top.

He was, he says, only having a good time. But when asked about his feelings concerning imports, he admits that it bothers him, “and if it don’t bother you, then you’re awfully stupid. … The American people, as a whole, should wise up and just realize that we got to do better, period. That’s the answer. Shame on us for just letting them beat us. We give them the technology and then let them beat us with it. Sure, it’s our own damn fault.”

The Asians, he concludes, “all stick together. Why don’t white people stick together? Huh? Not ‘til we’re a minority?”

I rise to leave as his 16-year-old daughter comes into the home and asks Ebens for a couple of dollars. Like most dads on most blocks he asks the obligatory, “What for?” as he is already reaching into his pocket.

Tomorrow will be much like today and all the others since he killed Vincent Chin. He will sit in his recliner and watch TV. The drapes will be drawn and it will be dark inside. Meanwhile, off in Washington D.C., 10 members of Congress were preparing to pose for photos as they demolish a brand-new Toshiba boom box, demanding that the U.S. cease being a “colony of Japan.” They would swing their bats with a gusto that would have put Ronald Ebens to shame.

As Ebens shows me to the door, he grasps my right hand firmly and, with his other arm, gives me a big, friendly squeeze. “Now, I don’t look like some killer, do I?”

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————